Design Sprints are a great way to help move your product development forward, or simply inject a boost of energy into your team when faced with a difficult design problem.

But they’re not the only option. And it might be that you’re not actually in the right position, or type of situation where a (standard) Design Sprint would have the desired outcome for you anyway.

So how do you know if a Design Sprint is the right approach, and what alternatives should you be considering instead?

First up, let’s get on the same page with what a Design Sprint is, and some of the reasons you’re likely to be considering running one…

What is a Design Sprint?

When you think of a Design Sprint, you’re probably thinking of the design process created by Google Ventures (GV):

“The sprint is a five-day process for answering critical business questions through design, prototyping, and testing ideas with customers.”

Using this process, each stage is tackled a day at a time over the course of a 5-day sprint, with the aim being that by the end of the week, you’ll have come up with a solution to your problem.

Design Sprints provide focus and direction

Design Sprints are a useful way to get a taste of what a UX process looks like - breaking away from the thought that you need to build the whole thing or have a fully-fledged requirements list before you start building. They give you energy.

Design Sprints also allow people who haven’t experienced UX processes before to see how their ideas get tested with users. And it can be an effective way of educating people working outside of UX Design to better understand user-centred approaches.

Product Development teams often use Design Sprints when they’ve been thinking about a problem for a while but haven’t been able to move it forward - allowing them to design and test potential solutions with users within a short time period. Just having the pressure of having to test with users provides a driver to (finally!) get it done.

Design Sprints also allow you to think outside the box more than if you were considering the whole problem and are a useful tool when you need to bring a multidisciplinary team of Tech, Design, UX, Marketing, etc., together to solve a focused problem, such as resolving high drop-off rates during onboarding.

The keyword here is focused.

If your problem isn’t well-defined enough, you’re not really in a position to be able to run a sprint. If you’re hoping a Design Sprint will help get that focus, you will be disappointed.

So, what can you do instead?

When to consider an alternative approach

As with most design methodologies, a Design Sprint offers a well-defined process. But you shouldn’t be afraid of adapting this process to suit your needs.

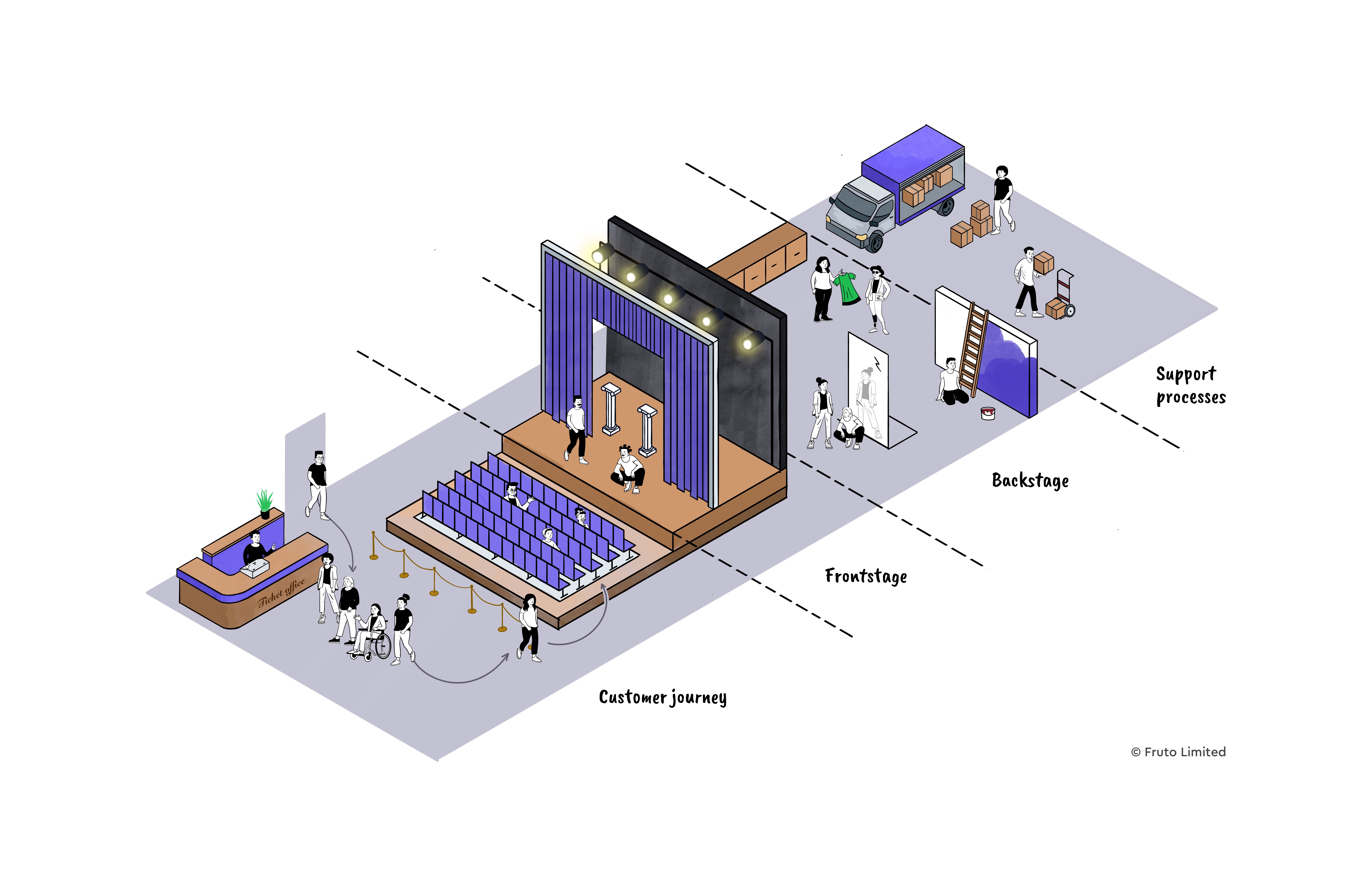

Whether it’s a tactical or strategic design project, there’s a whole toolbox of options available for you to utilise, and what we tend to do is take the Design Sprint essence and tackle each stage separately through a series of design workshops.

One of the main reasons for this is that the nature of the clients we work with often means that they have complex design challenges that simply cannot be resolved by rigidly following the 5-step, 5-day process.

Clients also often need help understanding what the right problem to focus on is and the difference between a problem (based on evidence) and an assumption before we’re able to help solve it.

Likewise, it may be that a Design Sprint is the right approach, it’s just not the right time. In this case, discovery workshops can be used to help you get to the point where you are ready to run a Design Sprint by bringing clarity to the specific problem that needs solving.

You don’t know what problem you need to solve

Design Sprints need to take place at the right phase of the project.

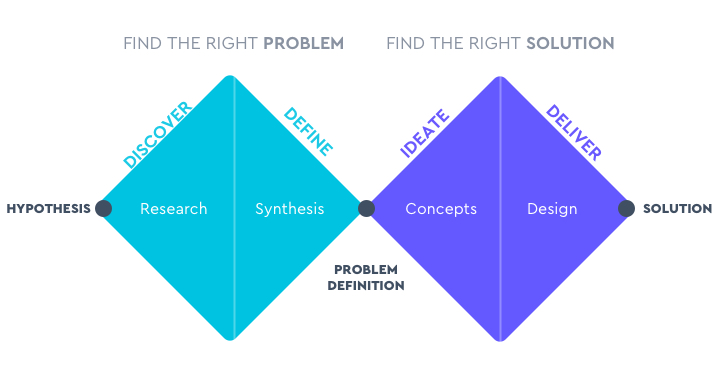

How focused and defined is the problem you are trying to solve? Often the answer to“why should I not do a Design Sprint?” is that the Problem Statement is too vague, and having open questions mean you may come up with premature ideas.

How much does the problem come from evidence (versus assumptions)? If you are assumptions-driven, you need more time to define the problem.

Having a well-defined problem is hugely important. Knowing you have a navigation, onboarding or conversion issue is not focused enough. An example of a focused problem would be “University students [target audience] are dropping out at stage X of the onboarding process. How might we improve the conversion rate from X% to Y%?”

Before you can start a Sprint, you need to be able to lock the scope down, and the only way you can do this is by knowing what the problem is, not just where it is.

You need more time

You also need to fully understand what are you trying to achieve in order to be able to choose the right UX techniques.

What is your ideal outcome, and how will you measure it?

For example, one phase of the sprint is to wireframe. It’s important that the team has been warmed up, is comfortable to sketch, and is ready to “catch things out”.

Preparation may also be needed in the form of analytics, user research etc, so people are up to speed and have a clear question to solve.

“How could we solve this problem?”

How well you know the problem will also help you to understand how comprehensive the prototype needs to be. For example, if you’re working on an app that deals with lots of data, a static screen won’t be able to be properly tested.

Really, 5-days is too short to solve most (complex) design problems. It could be 2 weeks with space between phases, or allowing more time to do the prototyping.

You also need to have users lined up to do testing (usually on the final day). This may mean recruiting 2-weeks before you need them for activities such as card-sorting, usability testing, A/B testing, etc.

Again, this serves as a useful reminder that a Design Sprint doesn’t strictly need to be one week in length - you can take longer if you’ll benefit from doing so.

How we approach Design Sprints at Fruto

At Fruto, the bottom line is that we advise using the right UX technique according to the project objectives and needs.

Our Design Sprints may be a 5-day sprint or a design sprint of 2 weeks, or we might run a series of stakeholder workshops. Flexibility in the approach is key.

To use a real-life example, we recently worked with an education client that needed to think more innovatively about what they were building and who needed support to improve the onboarding of their app.

They had a clear problem - users dropping out at a set stage - that the team had identified and which user data reinforced.

It was also helpful that we were an outside team as it meant there was no internal politics or background information bias to influence our decision-making, allowing us to bring fresh thinking to the problem.

In this instance, we first discussed the problem(s) with the representatives from each of the different business units on the team (Tech, Business, Marketing, Design).

We focused on getting their collective views on the problem, as they each hear the issue(s) differently. Some people knew the background behind existing issues, while others did not.

This helped the project group as a whole to understand and prioritise problems that needed solving and to come up with a question (problem statement) that was clear enough that it didn’t involve the solution.

We then ran an exercise where the group had to first think individually, then collectively - sharing feedback on each other's ideas. Potential solutions were then investigated, and then the best one(s) got prototyped and tested.

These types of workshops can be particularly useful when the project team is attached to existing legacy technology, previous decisions, etc., which they can find it hard to move away from. Relating to the vision of what the product could be - looking beyond the immediate tactical challenge to be more strategic - allows a new, shared vision to be formed.

Key takeaway: Adapt the approach to better meet your needs

There’s no doubt that Design Sprints are a useful design tool if you need to find a solution quickly and the problem you need to solve is well-defined.

But if you don’t really know the problem you’re looking to solve - you only think you do - then it’s likely that taking an alternative or adapted approach will better meet your needs.

A sprint doesn’t need to last 5-days. Nor do you necessarily need to follow the 5-stage process in order. Instead, you should look to adapt the process to meet your specific project objectives and needs.

Need help defining your problem? We’re here to help.

Find out more about our Design Workshops, or get in touch to explore working with us to tackle your big design challenges.